Perhaps one of the most interesting historical detective stories to be prompted by an item from the UHEC’s collections has been that of a mysterious letter written by a young man named “Alex” serving in the United States Army in post-World War II Germany.

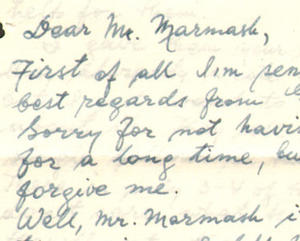

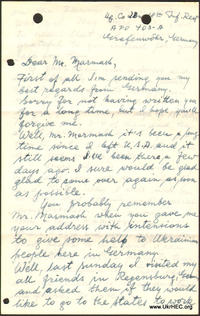

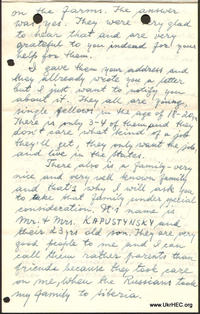

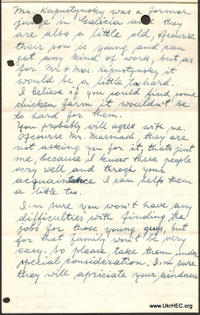

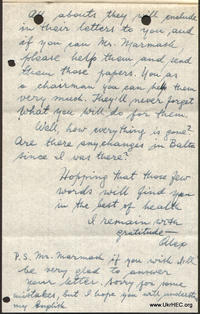

The letter is undated and does not have the author’s last name. However, it does have his military unit and address ("HQ Company, 2nd Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment/APO 403-A/Grafenwöhr, Germany") and we know that the recipient was Joseph Marmash, a Ukrainian community activist in Baltimore, Maryland. Mr. Marmash was also a member of the Maryland State Committee for the Resettlement of Displaced Persons, and that was the reason why “Alex” wrote the letter. He is asking Marmash for help in the resettlement of the Kapustynsky family, to whom he feels very close "because they took care of me, when the Russians took my family to Siberia." This must have happened in western Ukraine, because he indicates that "Mr. Kapustynsky was a former judge in Galicia." However, the letter also implies that Alex had lived in the United States and had spent some time in Baltimore ("Are there any changes in Balt[imore] since I was there?"). His written English is quite good, though not perfect (he admits in his postscript: "I hope you will understand my English."). Based on its archival context in the Joseph Marmash papers, the letter most likely was written sometime around 1949.

For anybody who knows the history of this time period, this letter raised a perplexing question. “The Russians [taking] my family to Siberia” from western Ukraine could only have happened after the Nazi/Soviet partition of Poland after the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939, but before the Nazi Operation Barbarossa invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. If “Alex” was, in fact, in western Ukraine at the time, then how in the world did he get to the United States in time to serve in the Army in the late 1940s? In short, the timeline just didn’t make sense.

We posted page images of this letter on our website in 2013 as a “Challenge to History Sleuths” and got some useful information from our fans about the possible identity of the Kapustynsky family and their arrival in the United States, but nothing about “Alex” or insight into his story.

The big breakthrough came when our archivist Michael Andrec sent a copy of this letter to his colleague Daria Labinsky, who was then working at the National Archives branch in St. Louis, which happens to house the non-active personnel records of the United States military services (she is now at the Carter Presidential Library). Amazingly, using only this scant information, she and her fellow archivists were able to find the Army discharge papers of a man named Alexander Riveny who matched the particulars of the letter. Some internet searching showed that a man of the same name and the appropriate age was still alive in the Los Angeles area, and we were able to find his mailing address. Michael then wrote him a letter explaining what we had found and enclosing a copy of the letter from the Marmash archives, and asking that he contact us if he was indeed the writer of the letter and wanted to share his story.

Mr. Rivney did call us in April 2015, and his story is in some ways even more interesting than we had expected. It turns out that he was born in the village of Ozeriany in what is today the Buchach raion of Ternopil oblast’, Ukraine. Shortly before the Nazi invasion of 1941, he and his family -- along with many other ethnic Ukrainians and Poles from the region -- were arrested, loaded into cattle cars, and sent to Siberia. His family had made a pact that if any of them had even the slightest chance of escape, then they would make a run for it and try to meet at an agreed-upon rendezvous point. Not long after, the young Alex did manage to jump off the rail car and get away despite a rain of bullets from the guards.

Not finding his family at the rendezvous point, Alex returned to Ozeriany where he lived hidden away at his aunt’s house. He had only been there for a few weeks when the Nazis invaded. As an able-bodied young man, he was soon taken by the Nazis as a forced laborer to the Vienna area, were he was put on a work crew filling in the craters left by Allied bomb attacks on German railroads.

When it was clear that the Red Army was approaching, he stowed away on a freight train that was heading west and ended up in the area of Regensburg, Germany, where there were already many other Ukrainian refugees. Since he was under the age of 18, he was classified as a “war orphan” by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) and therefore was put into the “high priority” pool for resettlement.

After arriving in New York and spending the summer at the Ukrainian Catholic seminary dorms in Stamford, Connecticut, he found a job with the Crown Cork and Seal Company in Baltimore, which is when he got to know Joseph Marmash. After re-connecting with a friend whose family had settled in Glendale, California, he moved there, and not long after enlisted in the United States Army. The Army had a need for multilingual individuals with knowledge of Eastern European languages, and he ended up stationed in Germany working in an intelligence unit and was eventually promoted to the rank of sergeant. It was at this time that he encountered the Kapustynsky family who was still in the Regensburg displaced persons camp. After his discharge from the Army, he returned to California, where he led a long life and was active in the Ukrainian American community of Southern California. He passed away a few weeks ago in 2020.

So, behind this mysterious letter is a remarkable tale of survival, luck, and perseverance.

Sources: Joseph Marmash papers; Alexander Rivney interview with Michael Andrec, April 15, 2015.