Life in Kuban'

Oleksii Balabas was born in 1890 in Slovians’ka, Kuban’, Russia, a descendent of the wave of Ukrainian emigration that followed the destruction of the Zaporizhian Sich.

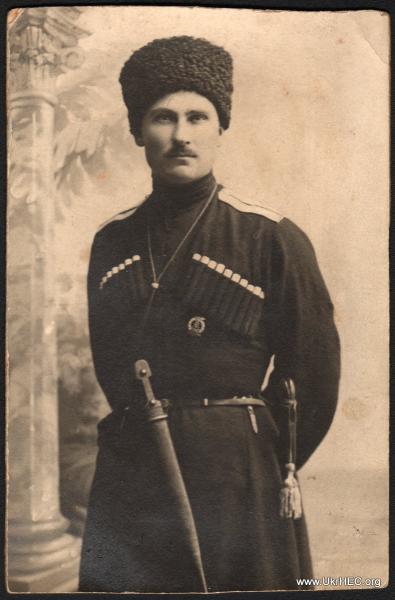

He married Ievhenia Pobidonostseva and was conscripted into the Russian Army upon the outbreak of World War I. He fought with the Slovians’ka cavalry regiment, first as an ensign, and later rising to the rank of "osaul".

The Balabas Papers contain a number of interesting items from this period, including his bank account books and legal papers related to the purchase of real estate.

After the 1917 Revolution he joined the government of the anti-Bolshevik Kuban’ People’s Republic, associating closely with many of the top government leaders.

Exile begins

Right around his 29th birthday in the fall of 1919, Oleksii's life turned upside down.

Members of the Russian ultra-nationalist and pro-monarchist Black Hundreds movement had taken control over some areas of the Kuban'. They immediately began to arrest and exile members of the Kuban' Peoples Republic and any other political organizations that did not agree with their ideas.

Oleksii was among them.

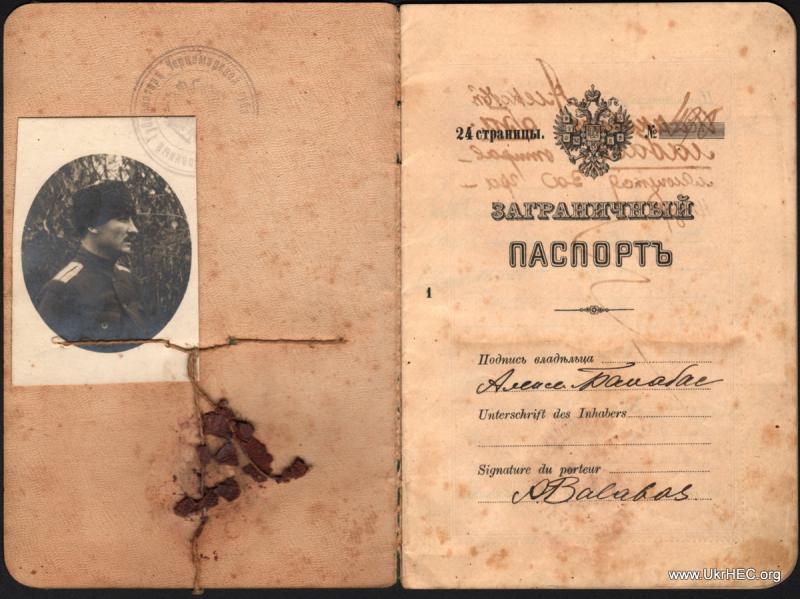

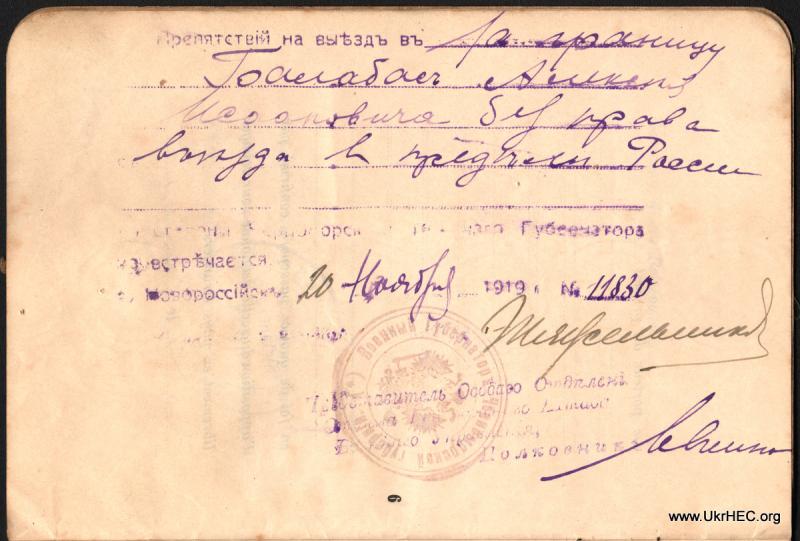

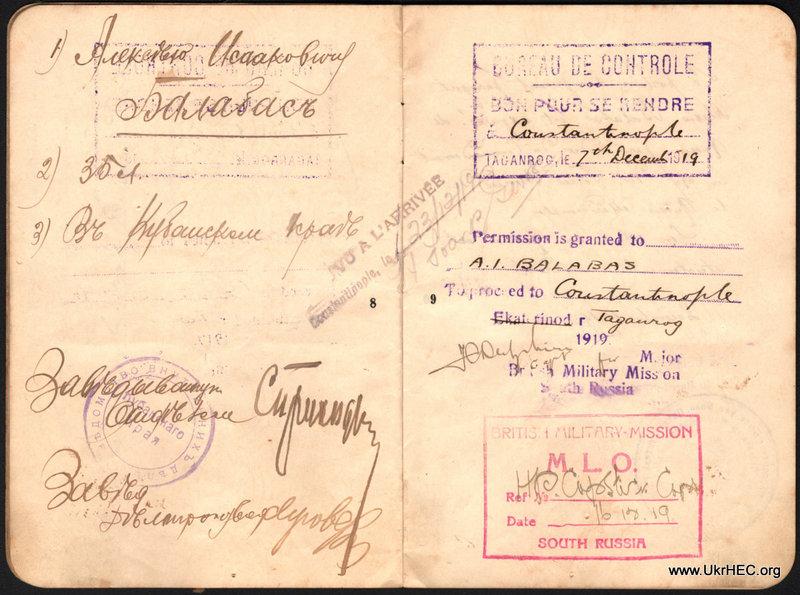

Oleksii was issued a passport, probably by a provisional Black Hundreds governmental office.

A stamp with handwritten text on page 6 states (in Russian) that he is permitted to travel "beyond the borders [of Russia] ... without right of entry into the territories of Russia". In other words, he is being exiled.

On pages 8 and 9, we see stamps from the British millitary mission giving permission for him to travel from Taganrog to Constantinople (Istanbul), and a note in French (across the spine) showing that he arrived in Constantiople on December 23, 1919. The British were involved because they were the military occupational force in Constantinople after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I.

Life in Prague

Oleksii did not stay long in Istanbul. Soon, he, his wife, and daughter moved to Prague, in the newly-formed country of Czechoslovakia.

Prauge had a significant Ukrainian exile community, many of whom were political refugees or veterans of the Ukrainian War of Independence. It boasted a vibrant cultural life, which included a bandura school lead by Vasyl' Yemets. This postcard photo of that ensemble from the Balabas Papers likely dates to the early 1920s. The woman 2nd from the left in the front row has been marked by an 'x' and may very well be Oleksii's wife Ievhenia.

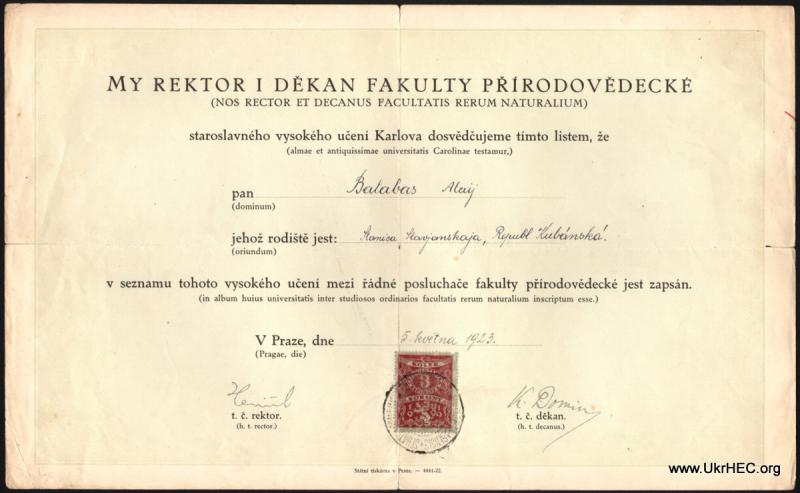

Oleksii worked as a compositor in the print shop of the social-democratic newspaper "Právo Lidu" while furthering his education. He eventually received a doctoral degree from the Charles University, and became teacher and administrator of the Ukrainian Gymansium in the Prague suburb of Modřany.

The Balabas Papers have course records and diplomas for both Oleksii and his wife, as well as their Czechoslovak and Nazi German identification documents.

The Holodomor letters

In the early 1930s, Oleksii managed to re-establish contact with his relatives back in the Kuban'. Many of the letters that they sent him (written in a heavily Ukrainian-inflected Russian) survive.

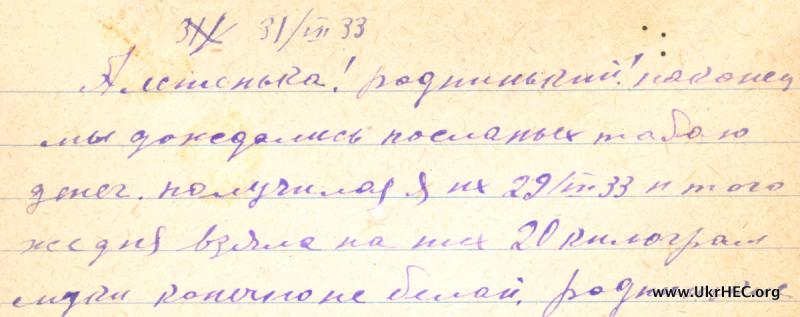

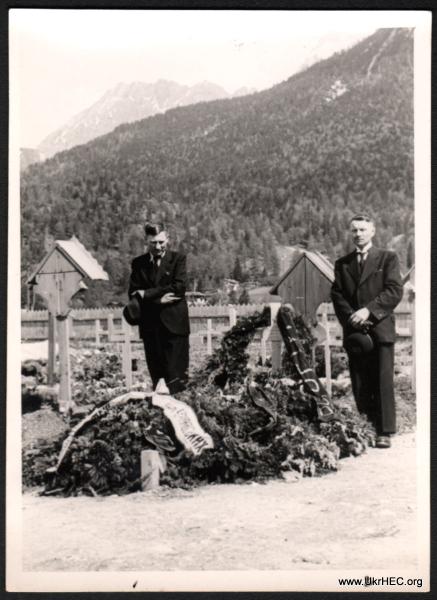

While most of the correspondence deals with relatively mundane personal and family matters, two letters written in 1933 are extremely important, as they provide a first hand account of the Holodomor that actually made it past the Soviet censors.

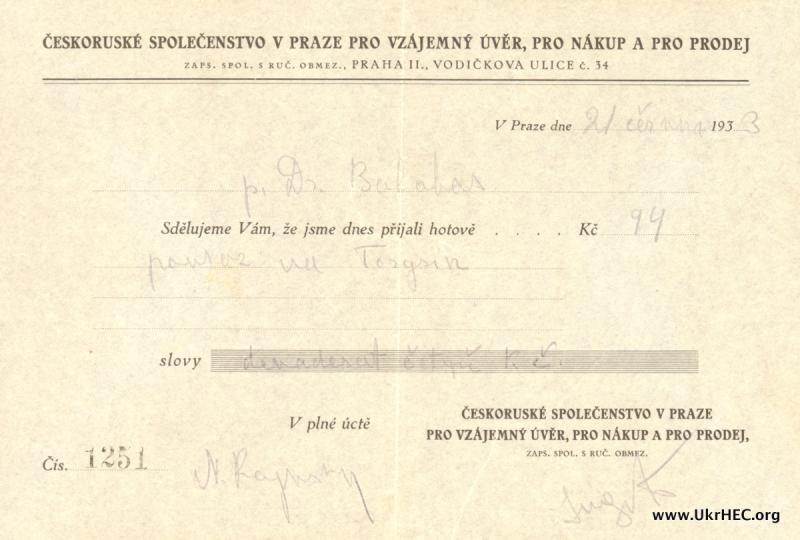

In a letter dated June 8, 1933, his sister living in Krasnodar describes how difficult it is to obtain bread. She also tells how those who have gold or foreign currency can purchase virtually unlimited quantities of wheat flour at the Torgsin (hard currency store).

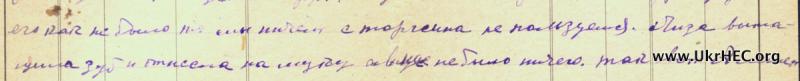

The detail shown here reads (in part): “Liza had a [gold] tooth pulled so that she could get flour...”

Oleksii responded by immediately remitting Czech hard currency to his relatives.

In a letter written a month later, the same relative can barely contain her joy at reporting that she received the money on July 29, and was immediately able to buy 20 kg of flour ("not white, of course").

In that same letter, the writer says that she was able to use the flour to make varenyky with the fruit from some fruit trees that they owned, and says (in the underlined sentence) that this was the first thing made out of dough that they had seen in two years.

Displaced Person

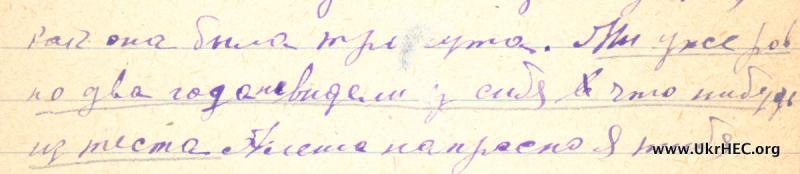

Fleeing ahead of the Red Army along with his fellow ethnic Ukrainians, he spent time in the Karlsfeld, Füssen, and Mittenwald DP camps. Given his advanced academic degree, he served as teacher and/or director at the Füssen and Mittenwald Camp Ukrainian Gymnasiums.

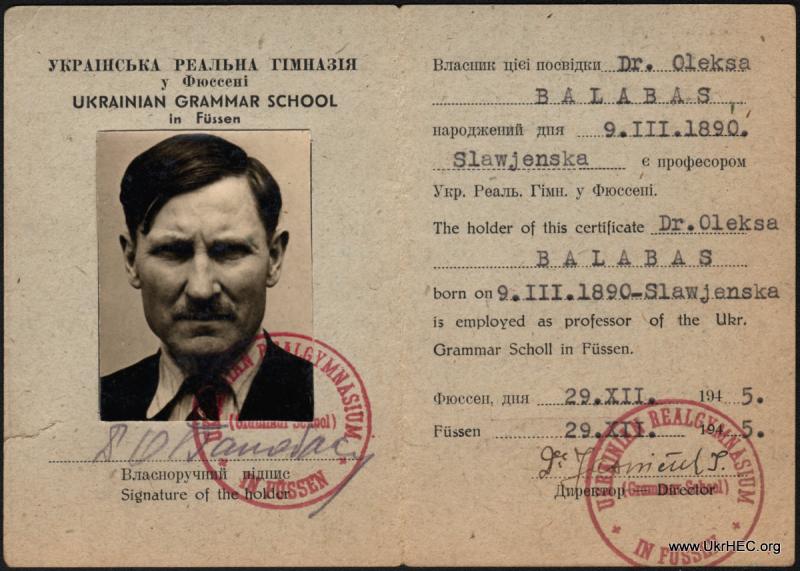

While in the Mittenwald DP Camp, his beloved wife Ievhenia fell ill and died. This photo shows Oleksii and A. H. Makarenko at his wife's grave on the second day after her funeral at the Mittenwald cemetary, surrounded by the scenery of the Bavarian Alps.

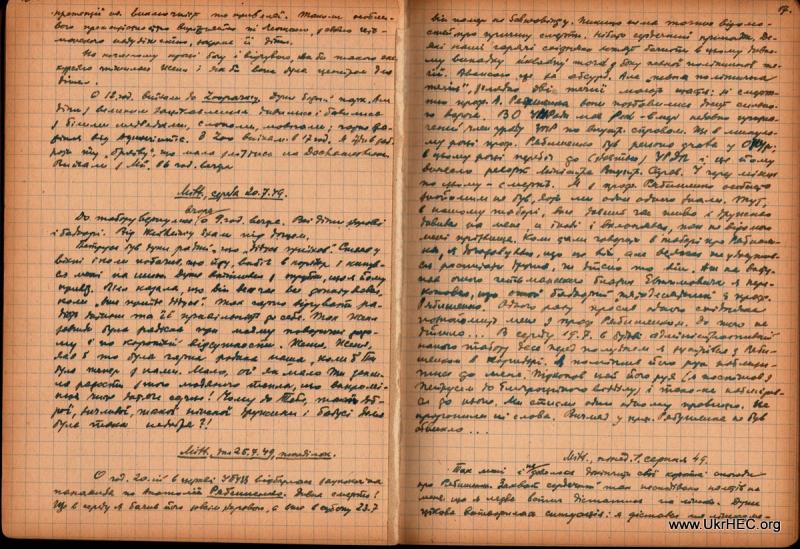

During this time, Oleksii kept a diary, partly to record events, but also to put down his thoughts and help deal with the psychological blow of the death of his wife. The Oleksii Balabas papers at the UHEC have six of his diary notebooks from this time and which continue nearly to his death, all written in his minuscule and often difficult-to-read handwriting. A transcription and translation of these important documents was begun in 2022 with a grant made possible by funds from the Somerset County Cultural & Heritage

Commission, a partner of the New Jersey State Historical Commission.

Resettlement in the US

One of the main goals of any DP Camp refugee was to get resettled to a country that was willing to take them in as an immigrant. Able-bodied and unmarried individuals in their 20s were able to emigrate fairly easily, but older people and married couples with more than 1 or 2 children were considered to be "difficult to resettle".

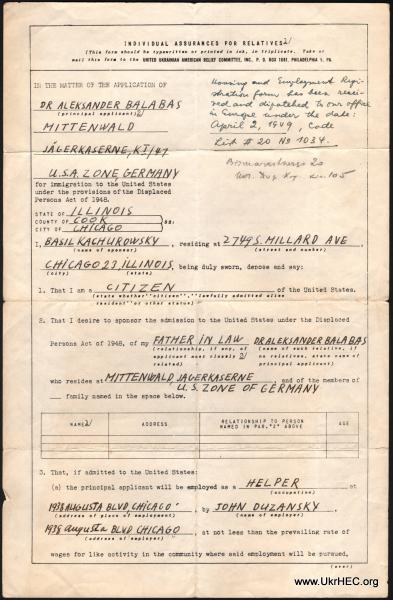

Oleksii, now nearly 60 years old, was definitely in the "difficult to resettle" category. To be allowed into the US, he had to provide an "Assurance" from a sponsor already in the US who would promise to provide financial support for the immigrant. He was able to get such a sponsorship from his son-in-law.

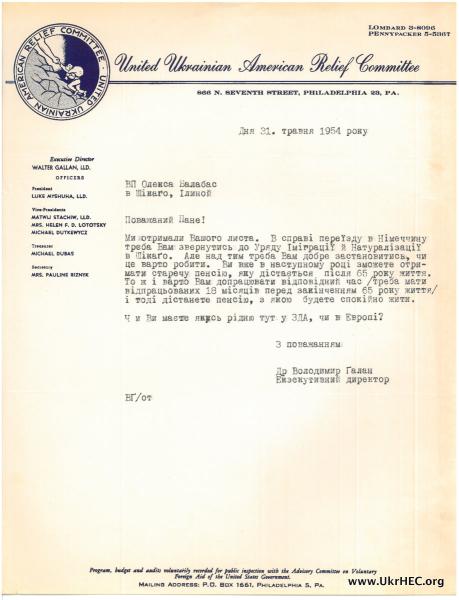

Various Ukrainian-American and Ukrainian-Canadian organizations were formed to help DPs immigrate to North America. One such organization was the "United Ukrainian American Relief Committee" of Philadelphia, who helped Oleksii reach the US.

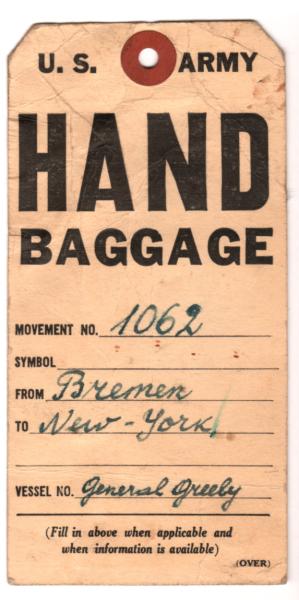

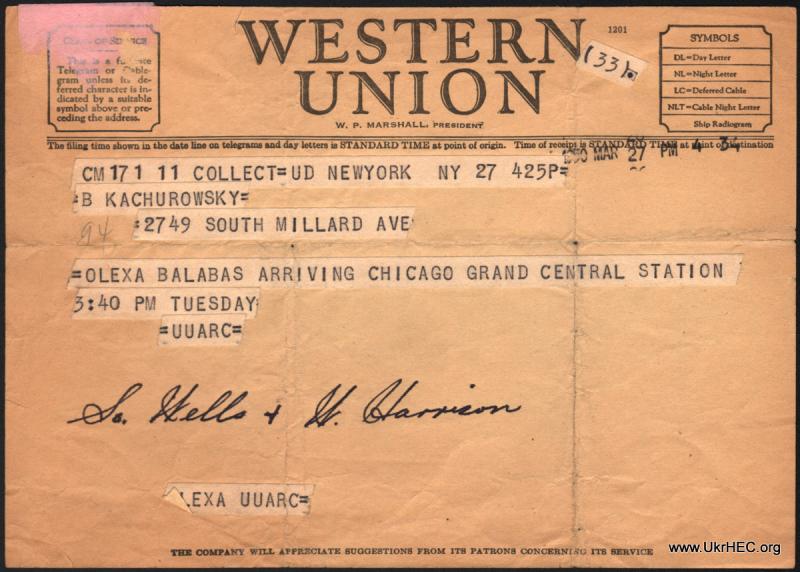

Oleksii crossed the Atlantic in 1950 aboard the "General Greely", and traveled by train from New York to Chicago.

He arrived in Chicago on March 28, 1950 to begin life in yet another foreign country.

Life in Chicago

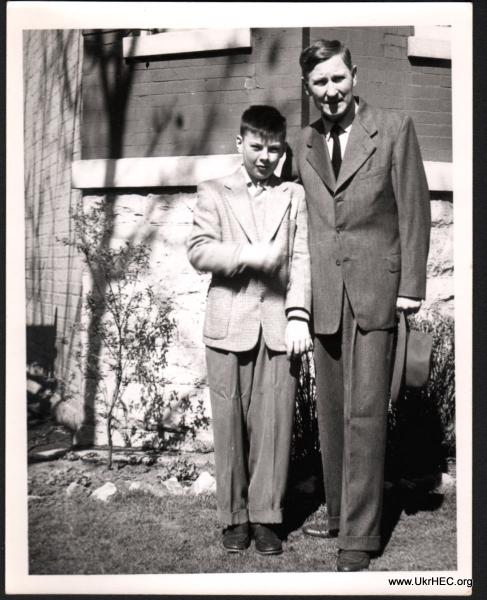

In Chicago he was able to be close to his daughter Liudmyla and his grandson Petro. He was able to find some work in the printing trade with the Czech-language newspaper "Svernost" and the print shop of Prof. Terlets'kyi, and also taught at the Ukrainian Orthodox school.

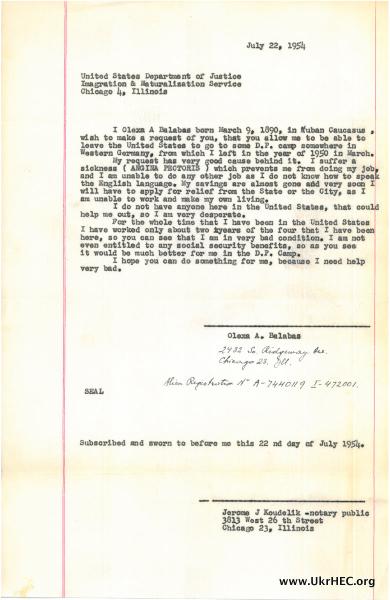

Unfortunately, life was a struggle. The fact that he had an advanced degree from one of the most respected universities in Eastern Europe was essentially useless for him, given that he had very limited speaking and writing ability in English. His health was also failing him.

By 1954, life had become so difficult that he even began to consider the possibility of going back to West Germany (with the idea that life in the DP camp was preferable to what he was facing now). It was too late for that, of course, and he remained in the US. He moved to New Jersey after prostate surgury and died on June 23, 1960.