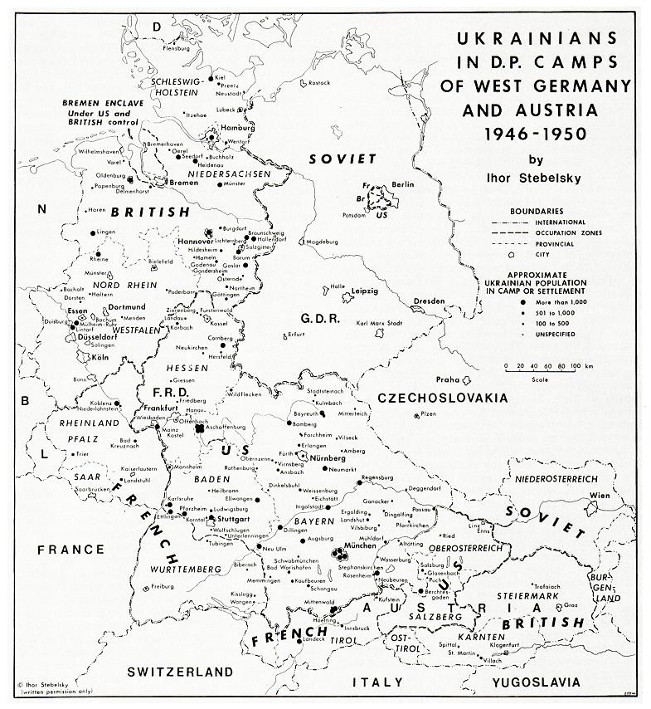

Locations of Displaced Persons Camps with Ukrainian populations after World War II

World War II initiated a period of great social and political turmoil in Europe. Ukrainians (from Eastern Galicia) who had lived between the two World Wars in the Second Polish Republic experienced unbelievable personal hardships and many died as their homes were overrun by both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Ukraine was in ruins. Many of those who survived were determined to leave all the chaos behind and emigrate to a safe, stable country where they could freely practice their religion and celebrate their culture.

On VE Day in 1945, there were tens of millions individuals that had been displaced by war. About 1 million, mainly from Eastern Europe, could not or would not return home (after avoiding forced repatriation). Approximately 200,000 of them were Ukrainians, who were interned in Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Austria and West Germany under the administration of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA).“Displaced Persons Camps” Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

The Third Wave of Ukrainian immigration

In 1944, the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (established as an umbrella organization in 1940 for the U.S. Ukrainian American community) formed the United Ukrainian American Relief Committee (UUARC) as an independent organization.Kuropas, Myron B. The Ukrainian Americans: Roots and Aspirations 1884-1954. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press, 1991. pp. 390-397. Along with several other relief organizations, the UUARC assisted in the resettlement of about 85,000 Ukrainian displaced persons in the U.S. beginning in 1947. About 8,000 settled in New Jersey.Rak, Dora. “Ukrainians in New Jersey from the First Settlement to the Centennial Anniversary”. In The New Jersey Ethnic Experience, edited by Barbara Cunningham. Wm. H. Wise & Co., Union City, N.J., 1977. pp. 439-440. This third wave of mass Ukrainian immigration to the U.S. continued until 1955. It should be noted that not all of these refugees arrived in the United States directly from Europe — some first resettled in countries like Argentina and Venezuela before finally getting the chance to come to the United States.

The character of this third wave was very different than those that preceded it. Rather then being economic migrants, these were primarily refugees who wanted to escape Communist rule. This was the first migration wave to include significant numbers of ethnic Ukrainians from central and eastern Ukraine (the previous waves were overwhelmingly dominated by people from western Ukraine and mixed ethnic areas of what is now Poland). They had witnessed the Stalin Terror and the Holodomor first-hand, and this had significantly contributed to their choice to flee.

The third wave was also the first to include many individuals who were highly educated and came from professional backgrounds. Unfortunately, due to language and other barriers, they often had to take menial, low-paying jobs to survive. They did, however, bring a jolt of intellectual and artistic energy to the Ukrainian American cultural landscape. This migration wave truly did bring “new blood” into the New Jersey Ukrainian American community. Although they became loyal Americans, they also maintained their spiritual connections with Ukraine, and the use of Ukrainian as an everyday language was revived.Rak, Dora. “Ukrainians in New Jersey from the First Settlement to the Centennial Anniversary”. In The New Jersey Ethnic Experience, edited by Barbara Cunningham. Wm. H. Wise & Co., Union City, N.J., 1977. p. 440. They joined existing community organizations, but they also established new cultural, political and financial institutions, and, in some cases, their own churches. At least initially, these third wave migrants mostly became urban residents in Newark, Jersey City, Passaic, Elizabeth, Perth Amboy and other cities already populated by Ukrainians.

They also quite literally brought new life into the community in the form of a large and concentrated baby boom. The birth rate among Ukrainian migrants of this wave had been artificially low due to the inhospitable circumstances of life during wartime and in refugee camps, but it exploded once they found a stable life in the United States. Essentially, the Baby Boom among the general American population that we commonly think of as starting in the mid-1940s was delayed and compressed into the 1950s in the Ukrainian community. Virlana Tkacz recalls, for example, how at St. John’s parochial school in Newark, the grade school classes just older than her had fewer than 20 students, while hers had over 70.Virlana Tkacz oral history interview. 2025. Ukrainian History and Education Center Archives.

An evolving equilibrium

After the mass influx in the 1950s, Ukrainian immigration essentially halted, mainly due to the fact that the Soviet Union effectively curtailed the ability of its citizens to leave the country. However, as in the period after World War I, the existing communities continued to evolve. Compared to the desire to Americanize and assimilate among the earlier immigrants, this wave had a tendency towards insularity. This was driven in part by the perception that Ukrainian language and culture was being destroyed by the Soviets, and that it was incumbent on communities here to preserve it. This fueled the growth of Ukrainian language schools, youth groups, and similar activities. Later in this period, this also spurred a tendency to human rights and other activism by individuals like Myroslav Smorodsky and humanitarian activity by groups like the Children of Chornobyl Relief Fund (founded by Dr. Zenon and Nadia Matkiwsky of Short Hills).Time Magazine, Notebook: Jul. 8, 1996. Kyiv Post, Children of Chornobyl Fund to shut down after 22 years. Jan. 12, 2012.

In addition, beginning in the 1960s, there was a steady exodus of Ukrainian Americans to the suburbs (Irvington, Maplewood, Livingston, and towns in Bergen and Morris Counties, and elsewhere). This ended up dispersing the concentrated Ukrainian communities in places like Jersey City and Newark and created a need for different kinds of community hubs. This led to a consolidation: some of the earlier gathering places (such as in Jersey City, Newark, and Passaic) began to serve a clientele outside of the immediate geographic neighborhood, while others were essentially new creations (such as the Ukrainian American Cultural Center in Whippany and the Ukrainian Orthodox Metropolia Center in S. Bound Brook/Somerset). It also led to the organization of mass-scale, state-wide events, like the Ukrainian festival in Holmdel.